Faith as Skill

Faith is stupid in modernity, but Christianity doesn't have to be.

Faith is “to believe without evidence” according to my Encyclopedia Brittanica Dictionary circa 1959.

This followed by second and third definitions of to believe and trust someone or thing, and to believe in God, doctrines of God, religion.

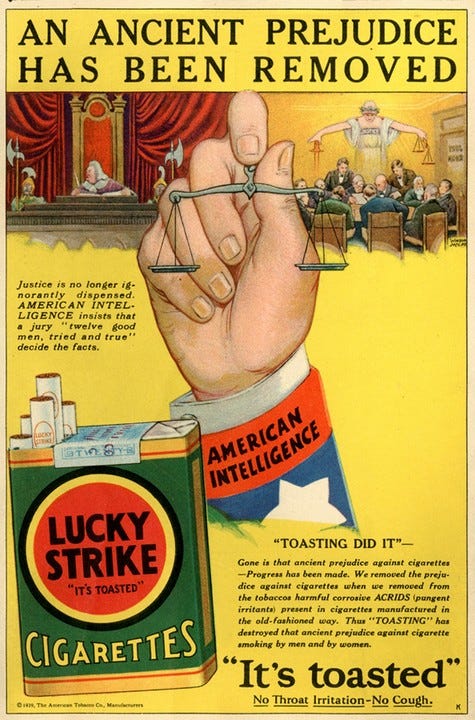

And so we see the devil’s handiwork. In the style of Edward Bernays and his Lucky Strike campaign, the adversary will just leave two things together and wait for our pattern making minds to associate. Faith—belief without evidence—is a sin in the scientifically wise mind. Evidence is king. Therefore faith in God (the second third definition), is guilty by association with the first definition.

Our world has accepted this sleight of phrase, and suffered the consequences. If it is immeasurable, it is irrelevant. If it is immaterial, it doesn’t matter.

Buried in this enlightenment humanism is the pernicious seed of autolatry. I am the authority, mankind declares. Our many judgements are the One, the Truth, the Reality.

Christianity has adapted to this framework causing mortal wounds to the Christian faith. As the West shifted to adopt this definition of faith—belief without evidence—it subsequently relegated objects of faith to the realm of meaninglessness.

With this shift, Christianity felt the burden to present in kind. Christian faith, theologians proposed, is based on factual evidence (more so than other religions), therefore it is right and true. The truth of Christianity was boiled down to its propositional accuracy. A far cry from what Paul wrote to the Corinthians.

The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God. 5 For what we preach is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, and ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake. 6 For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ.

2 Corinthians 4:5-6

While Christianity has remarkable historicity, its propositions still lie within a metaphysical framework that is at minimum immeasurable by modern scientific standards. This is the impasse.

Science and faith are not as opposed as we think, but because we place science as the ontological supreme, we cannot rationally have faith. Therefore Christians must choose faith over rationality. “Foolishness to the Greeks,” a phrase coined by Paul, has been employed to describe the reception of the Gospel in our culture.

The damage is not that Christians have worked hard to provide rigorous cases for their beliefs, but that faith in God has become faith in the lowest common denominator. Science believes in the observable, testable, repeatable. And so Christians have reduced their propositions to the same.

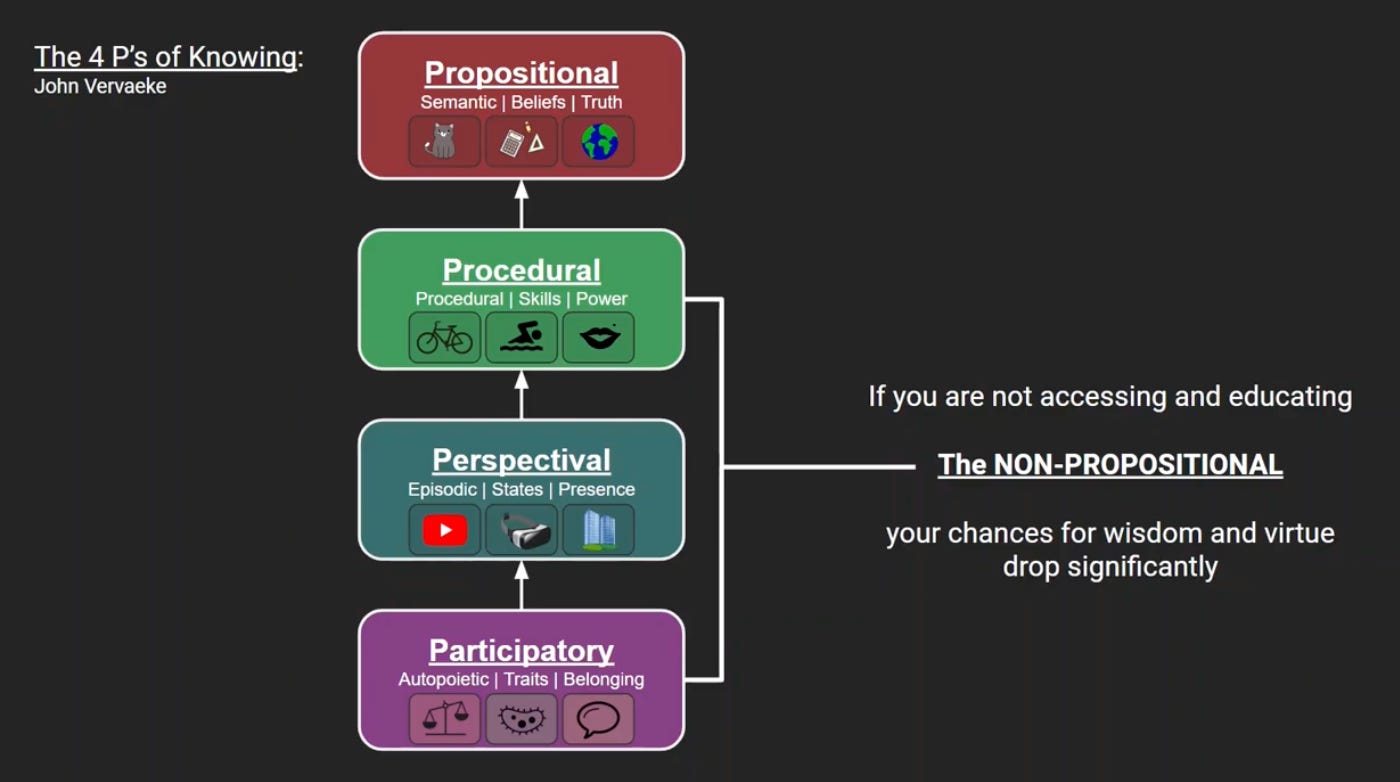

John Vervaeke has a beautiful framework of knowing.

Propositional - Knowing that

Procedural - Knowing how to

Perspectival - Knowing what it’s like to

Participatory - Knowing through being

This ladder of knowing doesn’t purport to rank the types of knowing, but they are useful for different situations. Knowing that is extremely useful for the material world. As is knowing how to. Knowing what it’s like to begins to shift towards the relational. And knowing through being even more so.

Vervaeke’s phrase “propositional tyranny” perfectly captures what I’ve been detailing in these opening paragraphs. We live under propositional tyranny, and the capitulations that were required of Christians centuries ago warped our doctrines to remain part of the cultural structure. Thus, objects of our faith have transformed from the personal: God and Jesus, and their promises, to the substantial: an empty cave, a shroud, an ancient tunnel, and several logically coherent arguments.

You cannot be a logically coherent argument. But you can be one with Christ.

Participation

When the idea of belief was shifted to the tyrannically propositional, the emphasis on the participatory faded.

Participation is what Peter says we have:

To those who have received a faith of the same kind as ours, by the righteousness of our God and Savior, Jesus Christ: Grace and peace be multiplied to you in the knowledge of God and of Jesus our Lord; seeing that His divine power has granted to us everything pertaining to life and godliness, through the true knowledge of Him who called us by His own glory and excellence. For by these He has granted to us His precious and magnificent promises, so that by them you may become partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world by lust.

2 Peter 1:3-4 [Emphasis mine]

The kind of faith Peter is not talking about is the kind that his fellow Jews had developed. It’s a kind of tribal notion that God loves us because we’re us. We think what we think, and God loves that. We believe what we believe, and God loves that. We are descendants of Abraham, and God loves that.

The kind of faith he is talking about is associated with the knowledge of God and Jesus. That’s the lever by which he calls us, and then through himself he grants promises, and through the promises (which are rooted in him) we can partake in his nature.

So, faith is not primarily a matter of knowing about God and Jesus. It makes sense, doesn’t it? If God is infinite, he is infinitely unknowable. This doesn’t mean we can’t know him at all, but that we certainly cannot exhaustively define him. And if he is infinite in nature we must have a continuous connection with him, such that our knowledge is fresh, or updated. Heraclitus said you cannot step in the same river twice, because the water flows downstream. What I’m driving at is something like that.

The river’s banks remain stable, but the content of the river is always changing, flowing, forever renewing. Its qualities change, too. Some days it's fast or slow, clear or muddy, high or low, warm or cold.

What is critical for knowing the river is stepping into it, not that you look at the river and say “Yep, it’s the same river.” Only by dipping in can you discern the current (no pun) state of the river.

What does dipping into God look like?

Practice

Early in my relationship with Jesus, I found Dallas Willard and John Mark Comer. Comer is one step removed from Willard, never having studied directly under his tutelage, but he carries Willard’s work to the world through his own writing. Comer’s emphasis on practice carries on the spiritual discipline “movement” of Willard and his colleague Richard Foster, among others.

Practices struggle to slot themselves into a religious tradition that is supposedly based on evidence, or knowing the right stuff. If everything is based on propositions (Jesus is God, and died for my sins, and resurrected) then practices are tricky to recommend. Especially in a culture of Christianity allergic to “doing”.

But doing is important in real life, so it inevitably reasserts itself as something different. Doing is not the primary means of receiving grace. Grace is freely given. Grace, Willard says perfectly, is not opposed to effort, but earning. A father who manipulates his son withholds affection until the son earns it by the behavior the father desires. A father who loves his son, does not want his son to be lethargic, but vigorously engaged in that which is good, his love remains constant regardless of the son’s actions.

Back to practices. Your life is made up of habits. You do what you do, and it becomes that much easier to do it again. Many people think of this in terms of doing what is right or wrong, but it is relevant in the domain of productive or unproductive, healthy or unhealthy, etcetera. There are less obvious value judgements attached to those last four terms. The value judgments are there, but they are less potent than the ones we associate with “right” or “wrong”.

Is it right to pray? Yes! Is it wrong to not pray? Sure. Is it helpful to think of these things as sort of zero-sum assessments of our “faith”? I’m not so sure.

Practices are excellent tools for participating in the life of God in our life—or, dipping into God. Scripture, communion, prayer, all these things are anchor points of our apprenticeship to Jesus. That concept of apprenticeship comes from Jesus’ great commission: “Make disciples (apprentices)… teaching them to do all the things I taught you.”

πίστις - commonly translated as faith in the Bible

I was reading 1 Timothy the other day. I’ve been thinking about faith, or pistis (πίστις), because of Jordan Hall. He’s been discovering a different meaning from our cultural norm understanding. As we’ve established, the mistaken understanding of our enlightenment world is that faith means adherence to something without scientific grounds.

This of course is a deep psyop by the adversary. Faith is the linchpin of life in the kingdom of God, and it’s been degraded to foolishness and whimsy.

Scientific evidence is the snag here. There may be no direct scientific evidence for the “existence” of God. The intelligent design folks will tell you that the gestalt is the evidence. The gestalt is precisely what is excluded from science. We prove things at the subatomic level, and work our way up. The gestalt isn’t unscientific, except that science cannot fit the whole picture under its microscope, so to speak.

I’ve come to think that material evidence has nothing to do with πίστις. What does have to do with πίστις? Practice.

πίστις (pistis) is a practice in all domains of life. (This is what I’m ripping from Jordan, to the best of my ability.)

A family budgets faithfully, and each month they meet (or fail to meet) that goal through a set of practices. A skateboarder develops πίστις through repetition. A dancer, a musician, a plumber. All these are examples of πίστις, and what we might call skill.

The thing with skill is it’s something that we have when we are particularly capable of doing something that doesn’t just happen. It is definitionally agentic. It is extremely relational. We have skills related to innumerable domains.

Scripture says that faith is the gift of God. Yes. But it is no different with skills.

Let’s take the skateboarder. We think of them as riding or falling. In reality, they are falling the whole time. What goes up must come down. The way that they fall is what is beautiful, creative, impressive. It’s the same with all of life. Music builds up, and eventually falls silent. A book must end, and if it is good, may be picked back up, physically or thematically by another author. A plumber patches up what is broken down.

All we do is an exercise of skill. Faith is the skill of participating in relationship with reality. Propositions are assertions about reality. It’s the difference between me yelling at Josh Allen to throw the ball, and Josh Allen facing 11 bloodthirsty defenders. One requires skill, the other does not.

We’re at the part of the piece where I’m supposed to make a proposition: this is how we should proceed. Alone in my office it’s tempting to assert what I think would be the best way forward for humanity. But I’m learning that the truest path forward is participatory.

We can propose, and develop procedures, and share perspectives till we’re blue in the face. Those things are empty if they are not in service of crafting and cultivating participation in God and one another.

I don’t know, and you don’t know, but together we can know and be known by the Knowingest One. And through that we may partake of his divine nature.

P.S. I’ll have a part two out soon, if not three. So sign up here.